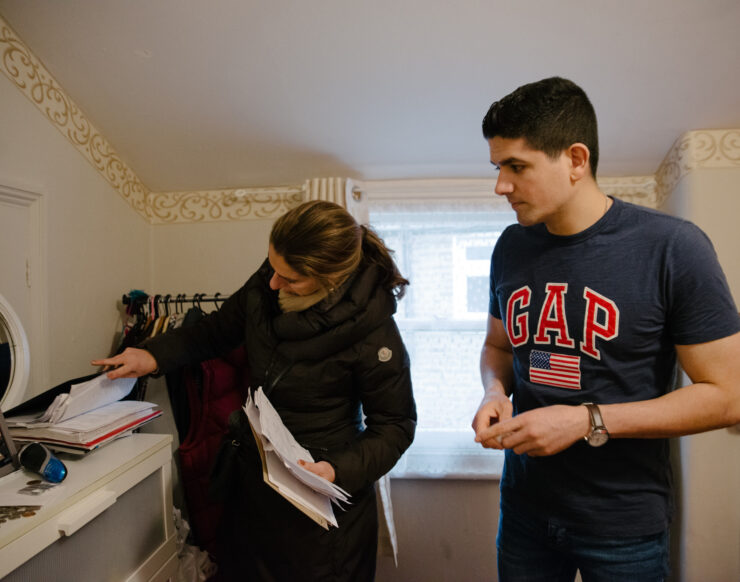

A collection of twelve stories highlighting the key emerging themes of the research from the experiences of both those that are 'new' to Europe and those that 'welcome' them.

As a crisis within a crisis, austerity has in many ways multiplied the risks and obstacles newcomers face when arriving in Europe. It has also, to varying degrees, sharpened the working and helping conditions of many civil society organisations in Athens, Berlin and London.

The repercussions of a European austerity politics have been most pronounced in Athens where state services have been working under straining financial pressures for years with particularly harsh effects on infrastructures of care. Aggravated social problems such as homelessness, unemployment and addiction risk further marginalising the already marginalised. For newcomers, austerity renders their situation even more vulnerable, making it harder to find permanent housing or employment. Moreover, due to increasingly restrictive EU migration regulations, many newcomers who wanted to travel north are now stuck in the city, leading to even more people in need and even less to give.

We regularly have local volunteers helping us out through the Scouts of Greece, and at the moment, we’re in a good place, but our shelter has been through some difficult phases. Our employees weren’t paid for six months in 2016, and when I started working here we couldn’t afford to pay for broken windows. We’re all working on four-month contracts; some have been doing this for 7 or 8 years. It’s a harrowing experience. How can I plan something that can take a year when my contract ends in 2 months? How can you provide services when you are not paid and you have a child at home? You live and work in constant uncertainty, which you need to turn into certainty so that you do your job properly.

I need five different medications but not once have all those been available. Sometimes they give me three or two, and when I am lucky, four. I call this ‘Greek style’: one month they have it, one month they don’t. They tell me to buy the rest privately but there is no way I can afford that. I currently get 150 Euros per month to sustain me, but I send 100 Euros to my wife in Syria and I’m their only source of income. So, I have only 50 Euros a month to cover all my food, transport, everything...

(Athens, Muhammad)

I have been in Greece for just over 1 year now and my asylum claim has been accepted — I am just still waiting for my ID — but I see no future for me here. To tell you the truth, I did try learning Greek, but I think to learn a language that is so different to your own, you need to have the motivation to do it, to see yourself living here. You are meant to leave the camp within 6 months of getting your ID but they’re not even enforcing this rule. This is Greece, there is a financial crisis. There are no jobs. They know they will just end up increasing the number of homeless people on the streets, so they don’t enforce it. How will I find a job here when Greeks can’t even find jobs? How will I bring my family here?

(Athens, Muhammad)

While the economic situation is less dire in London, UK austerity politics has nevertheless put immense pressure on newcomers and their supporters. Austerity not only impacts the level of practical support that people can offer but risks undermining very much needed emotional connection as well. And newcomers in London report on the effects of austerity, particularly for social service and educational provisions.

I feel like I need to deal with the problems of the people I support completely on my own. My phone is always ringing. I’m currently being paid to support six families in Haringey, but the previous families are still calling me, nearly every day. It’s quite tiring and emotional work. I’m more than a translator, I’m like a social worker. Sorting out phones, bank cards, GPs, benefits… it takes about 6 months until they kind of settle in.

The agency I work for is hired by the council to support the resettled families. I just fill out timesheets and they send me my pay. No one asks me anything. Once, I felt like there was an issue that really needed to be raised, so I sent an email. I got a response thanking me, but there was no meeting to discuss it. It’s very frustrating. I end up spending the little time I have for myself researching online for the information the families ask me about. It’s tiring but I feel happy to do it, to help them feel relaxed instead of worrying. My friend told me I need to learn to have boundaries, and I do try… but I’m so tired.

(Saana, London)

In their first year of school, the children had lots of after school clubs and activities; swimming, dancing, football. This year, they will only have football club as the swimming and dancing are not offered. We were told they were being cut because of funding. They also sent us a letter saying the children will be served smaller portion meals at school, and we should supplement their lunches, if we wanted.

(Leila, London)

When he first got to London, no council would help him. You have to have that local connection to a borough, otherwise they don't help you find housing. You have to have lived in an area for six months first. And as a single guy, he would have been very low in the list of priorities. This would have been for families, vulnerable people, elderly, disabled, women. And to get a private flat, you need to pay the rent up front, and the deposit, then you apply for housing benefits. So it’s very, very difficult. Through my work at the Refugee Council I know that a lot of refugees become homeless. I had come across Refugees at Home through my work before, where they find people with empty rooms to host refugees, and put Reza in touch. It's a fantastic organisation, I speak really highly of them. Reza got very lucky because Miki and Miriam’s family was really, really lovely and they’ve been so good to him.

(Reza & Catherine, London)

Things are improving with the current local administration in the Council, but at one point relationships with civil society organizations were really strained. The council was introducing lots of cuts and started playing organizations off against each other, creating favoured and non-favoured ones. To stay on the right side of the Council and continue to receive funds, you had to accept a lot of cuts. But to try to be slightly generous to the situation, the funding cuts on the councils are horrendous, and they aren't stopping. Now, if those funding cuts were not in place, whether that would lead to any different outcomes... I don't know. I think holding local government to account, citizens holding local government to account is absolutely essential.

(Haringey neighbours, London)

In comparison to Athens and London, newcomers and social workers in Berlin have not experienced austerity in the same way. However, with its chronically empty public pockets and relatively high unemployment, the city nonetheless struggles with a variety of social problems which hit newcomers in particularly harsh ways. Most notably, Berlin’s housing crisis and on-going gentrification processes make it harder for newcomers to find their own flat. Moreover, newcomers frequently talked about the ways in which they felt pressured to be economically productive rather than forming their independent paths.

I don’t like living in the shelter at Tempelhof* – it’s a constant reminder that I’m a refugee here. I don’t have a problem sharing a room, but I don’t really get along well with my roommate, so I’m asking to change rooms. My friends and I sometimes think about moving out together for more private space and actually feel like home. The refugee office (LAF) can also pay for an independent flat instead of the hostel. But, it’s Berlin — everybody is looking for a flat! And there’s definitely discrimination. You show landlords your LAF documents and suddenly they give the flat to someone else.

* Tempelhof Field is the site of a former airport in central Berlin that was converted to emergency shelter for refugees by the government.

(Sadu, Berlin)

While going through the legal process to have the gender transformation operation I was working at a hotel. My life was work, papers and gym. Finally, I got the approval from the courts, and I started the medical procedures and hormones. That’s when the hotel fired me all of a sudden, because I took extra sick days. They didn’t even give me any notice. The payments started piling up and the job centre was horrible. They kept on asking me to do things beyond my current capacity, physically and mentally. That’s when I broke down. I broke down and I haven’t been able to stand up completely since.

(Ali, Berlin)

Two years ago we got funding for a project that covered the accommodation and health insurance of participants who have no access to these things. In Germany, some refugees have more advantages than others, like Syrians at the moment. But even the Syrians that come and work with us, they are the more disadvantaged Syrian refugees. The ones that lost the opportunities they had within the government schemes. So we try to help them with their last chance by giving them training and workshops that will help get them into technical apprenticeships schemes.

(Hussam, Berlin)

There is the element of feeling that I need to prove myself here, prove who I am and what I can do. At home, you don’t really need to do that, you know? You can feel comfortable. But here there is a constant need to prove that we are not what the media portray us to be. We are not criminals or here to take money from the state. Germans also think we are using their taxes to eat and hang out in restaurants having fun. We need to show them that we are not here to waste their money. That we have escaped war. That we are enterprising and will stand on our own two feet, support ourselves. I am most proud of the fact that I have been able to show this. To prove this.

(Malaka, Berlin)