A collection of twelve stories highlighting the key emerging themes of the research from the experiences of both those that are 'new' to Europe and those that 'welcome' them.

It is difficult to provide a concise summary of something which has so deeply and severely shaped the lives of the newcomers we have met in Athens, Berlin and London. Having to flee and migrate because of war and destitution, leaving your home and often your family and friends behind, is not only an unimaginable tragedy but far too often a reality that many people around the globe are facing. Experiences of death, violence and fear both in war as well as while migrating can destabilise the very core of selfhood, making you lose a piece of yourself. The severity of loss and trauma further shows the urgency for host societies to support newcomers in setting up a stable life, finding a decent living and building meaningful connections – all of which is too often delayed and hindered by the manifold challenges and obstacles newcomers encounter in their cities of destination.

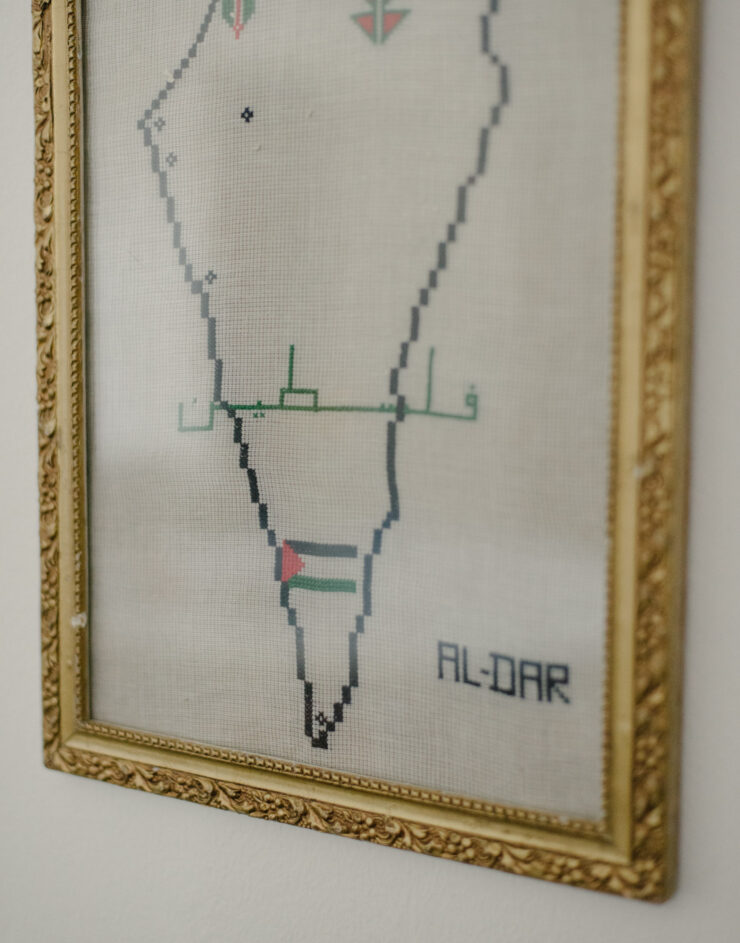

FEELINGS OF LOSS

The feeling of loss can in many ways cause despair, anxiety, depression and long-lasting trauma which only become aggravated by often distressing experiences of migrating and arriving in a new, unknown place. As such, feelings of loss have become the constant companion of newcomers who are aiming to deal with their past experiences while also building a new life for themselves.

On New Year’s Eve, after we’d only been here a few weeks, there were fireworks going off. You should have seen the children, they were shrieking – all of them – they thought they were bombs. I had to explain these were for celebrations, not war. I am happy to share with you anything you want to know. But our story is a sad one. There is a lot of misery, a lot of pain. The war in Syria and everything we saw there... Owais, he was maybe 8 when his elder brother died right next to him from a bomb. Then, when we ran to Lebanon, what we had to face there… it’s been a very hard journey.

(Leila, London)

I don’t have many friends, not since Sima left. This loneliness is the worst thing I think. At the shelter, they once gave us free tickets to an exhibit at this museum. I didn’t understand it but I walked all around and took lots of photos. But then I sat outside with my mini shisha, watching people go by, and feeling lonely. Sima was at the shelter before I arrived and we became very close, very quickly. She’s in Germany now, she got resettlement there. I miss her all the time. How do you deal with the loss of a friend? I can’t just be sad about it. I won’t survive if I dwell on it. So I sing this Egyptian song to remind myself:

We meet people, and we say goodbye,

This is the cycle of life

(Rana, Athens)

Actually, it’s not entirely true that I arrived from Syria with nothing, I came here carrying bits of the war in me. Seven pieces of shrapnel from bullets. The doctors here removed six that I still hold on to. The seventh is lodged too deep and the doctors felt it was better to leave it than try to get it out.

(Anas & Muhamad, Berlin)

RECOGNITION OF TRAUMA

Despite its pervasiveness in the lives of refugees, the trauma of loss is rarely adequately cared for or even recognised amongst the political and administrative authorities in Europe in charge of managing migration. While civil society actors and local support groups usually have a better understanding of this, they too often neither have the knowledge nor the resources to sufficiently help people deal with trauma. The extent to which resources of care are accessible for newcomers suffering from loss is furthermore dependent on the general availability of support services and can vary quite extensively. In Athens, given the general precariousness of much needed institutionalised assistance, psychological support is difficult to access and thus often stems from relationships between different newcomers and/or local activists. In London and Berlin, while such help is certainly more available (in theory) to a greater extent, in practice, these were often difficult to access due to institutional barriers, and a politics of austerity. A general lack of awareness and empathy, issues of translation or the pressure on newcomers to 'just get on with it' reflect crucial barriers that often leave people alone with their loss, relying on their own devices, networks and strategies.

Different groups of refugees have had very different experiences arriving here. The ones who flew here from Lebanon in the 70s/80s had easier journeys, they just took a flight. But when they arrived they were rejected and isolated. The Syrians and Iraqis now have had very difficult journeys, but once here they found a politically welcoming environment. The Lebanese refugees were concerned with issues of residency, risk of deportation and constant instability. This led to endless other problems, many of them familial, such as divorce and attempts to marry Germans for residency. The Syrians and Iraqis today are dealing with other traumas, whether it is from their journeys or the wars they’ve witnessed and experienced.

(Renée, Berlin)

The first few months here, there were so many appointments. And the forms, my god! Going here and registering, going there and registering. Appointments, appointments, forms, forms. It drove me crazy. All I wanted to do was sit at home and tidy up the house. To settle. To breathe. There was too much pressure sometimes, at the beginning, with everyone wanting us to get going so quickly. I just wanted to tidy the flat all the time.

(Leila, London)

I had a mental health condition that was causing the hair in my beard to fall out. The doctor told me to take this medicine for four months, but it costs 70 euros a month. We can’t afford it, so I only took it for one month. My wife’s been diagnosed with a medical condition too, and there’s nothing we can do. None of the organizations here are able to treat her. Her sickness is always on my mind. I want for us to be in a safe place and settled where she has access to medical care.

(Tareq family, Athens)

I’ve been working here for 12 years and I can’t imagine working in any other school, where parents are more concerned about teaching methods or whatever… I hate that. Education is not the most important thing, it’s about being in an environment where they feel safe and happy, and can interact with other kids. This role of an educator is like a social worker. One boy’s father came yesterday and said his kid is waking up at six to come to school, he’s so happy to come! There are many kids that come from war zones and have never even been to school, so the impact for them is really big, it’s something stable in their lives. So, okay, sometimes I do mind when they touch everything, but I also don't mind. Because they need to do it, they need to play.

(Natasa, Berlin)

THE 'UNGRATEFUL REFUGEE'

Some civil society actors identified these missed opportunities to care for trauma as also jeopardising possibilities of integration more broadly. Civil society actors generally deplored a lack of training and preparation which would make it easier for them to deliver appropriate care to newcomers. In Berlin, in particular, many also identified that, despite an earlier 'refugees welcome' public discourse, the failure to make space to accommodate trauma in the integration process, led to exaggerated expectations and disappointment. There has been a U-turn in public opinion as the discourse of the 'ungrateful refugee' has been capitalised on by the alt-right.

You may see me laughing, but I am not in a good place. I’m very depressed. Sometimes I think, ‘I am 28 years old and I have already seen all those things.’ I’m strong, it’s true, but also I feel like nobody sees me, nobody touches me. And this is when you start to feel like all this is for nothing. I’m asked for so many things here. Integration, fine, I’ll do that. I learnt German on my own, I didn’t go to school. My language is not perfect but I managed all my papers on my own without a translator. But just give us some space, that’s all. We are coming from war. We have seen things no human should see. From a completely different place, culturally and religiously. You can’t switch these things off. Even for someone like me — my body changed, but my memory persists as ‘Ola.’ My feelings about the things the government wants from me will be different to how they see it. How to reconcile this, I don’t know.

(Ali, Berlin)

The welcoming environment in 2015 was a very positive development, but the problem was that Germans hosted newcomers in their homes without being prepared on what to expect or how to deal with trauma. They expected they would come stay and be thankful all the time. There was no understanding of conflict and its aftermath, of the psychological journey the newcomers were going through. They had lost family, friends, property. They were having to make sense of what they just experienced and what they are now receiving. So then the people who opened their homes, with good intentions, started to withdraw their welcome. In many cases, unfortunately, they turned the other way, to the right. The welcome was genuine but it was not supported well. I believe it was a missed opportunity.

(Renée, Berlin)