A collection of twelve stories highlighting the key emerging themes of the research from the experiences of both those that are 'new' to Europe and those that 'welcome' them.

Digital technology, particularly social media, is essential to migration for navigating new lives, connection and solidarity. Yet, digital technology has equally opened up unprecedented possibilities and strategies of surveillance, of monitoring, controlling and detaining people. The risk of surveillance – especially in the context of war, rebellion and migration – too often means risk of life, too. The need to be and feel connected via digital media while fearing the consequences of surveillance puts people in the ambiguous position to negotiate their own digital practices in particular ways, putting themselves out there while not disclosing too much. And with increasingly smart surveillance techniques and the growth of big data technology such risks will only intensify, making acts of resistance, of connection and indeed, of migration evermore precarious.

SURVEILLANCE AS A WEAPON

Many of the newcomers we met during our fieldwork fled their worn-torn home countries where they had found themselves in constant danger of surveillance. Due to the life-threatening situations in their home countries, many people ventured on their journey to Europe in the hope of a safer, sounder, more peaceful place.

Many of my friends share every minute of their lives on Facebook. Social media platforms are important for connecting, but this is excessive. It feels like it’s acceptable now for people to be watched and monitored all the time and people are willingly participating in it. There is no need for CCTV cameras anymore, people post their whereabouts themselves! I’m really uncomfortable with that, especially about children. When I post things I’m careful not to share information about where I am or where I’m headed. Sometimes I post photos of myself, but the photos I post are months apart. I’m always consciously trying to protect my privacy.

(Malaka, Berlin)

The situation in Turkey is getting tougher for everyone. It’s transforming into an Islamic State and for Kurdish people it is even harder. Monitoring and surveillance are everywhere, we are constantly being watched. No matter what you write on social media they can catch you and jail you. Thousands of people get jailed, they are constantly building new prisons.

(Aynour, Athens)

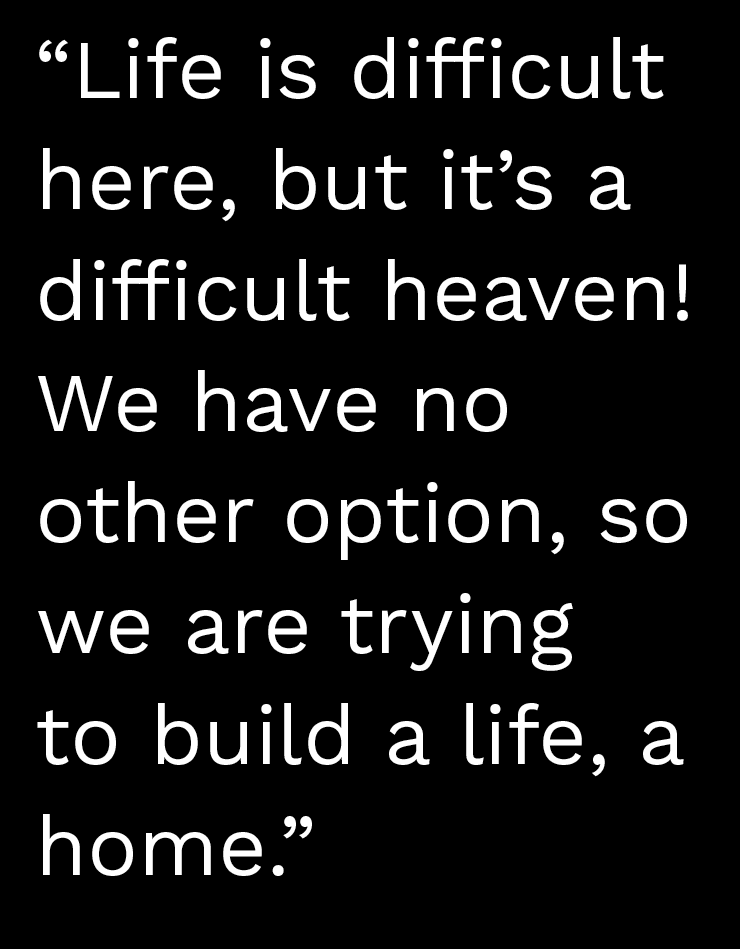

When the revolution started, I posted my thoughts on Facebook, but even mild criticism is considered traitorous opposition and someone reported me to the local police. We call them ‘the fifth pillars’ — those who report on people around them. My family has a history of opposing the government and my brother was a political prisoner — he was killed in the Tadmur prison massacre in the 1980s — so it was not safe for me to stay. My wife and children went to her parents’ home, and I went to Idlib. We expected it all to be temporary. That was four years ago and it was the last time I saw my family face-to-face.

(Muhammad, Athens)

I’m very careful about using the internet for politics. I use proxy servers and tape the camera. I have two Facebook profiles: one I use to connect with family and friends, with my real photo and real name, and another anonymous one that I use to keep up to date with political news from Syria. The regime regularly publishes lists of people confirmed dead, and I always go through them to find out if anyone I know is on them. There are lots of videos on Youtube. You can even find the hospital where my dad was staying, the one that was bombed. You can see videos of people searching through the rubble for survivors.

(Hadi, London)

The last year I was in Syria, I was all alone and scared all the time. Till now it hasn’t left me... the fear. Using the internet attracted unnecessary attention so I avoided it. Even in Turkey, it took me three months to feel I was safe enough. Other people are cautious because they still have family in Syria, but I have no one, so one day, I posted so many things to Facebook. I had to share what happened to me. So I criticised Bashar al-Assad, everyone. And I felt so relieved after. Now I like sharing. I share lots of photos of my life, like when we all go out, and sometimes at the café if I manage to make a really good cappuccino.

(Abohanna, Berlin)

POLITICS OF SURVEILLANCE

A number of newcomers expressed great concern about safety and security on social media. In response to these concerns, they either avoid social media altogether, or engage in self-censorship to avoid endangering themselves or their families back home. Some people more concretely express their anger to Europe’s complicity to expansive digital surveillance. Surveillance, they said, inevitably pushes them away from certain people and places deemed as dangerous by the state and deprives them from free speech and political agency. While some of those who raised concerns on surveillance developed strategies to avoid it, others chose to take risks rather than being silenced.

The resettlement route in other EU countries has been closed since the Dublin agreement. My biometrics were registered when I first arrived in Greece and because of that I can’t settle anywhere else in Europe. Wherever I go they will scan my info and see that I’ve registered in Greece already. I’ve been told there is a way to cancel biometrics data so you can register in another country, but I don’t know how you go about doing that. The main problem is there is no clarity to immigration law, nothing you can depend on to argue a case. I can’t say, ‘under section 2 of law 4 I have a right to...’.”

(Muhammad, Athens)

When I first arrived, I was told that all of this was staged so that Western governments like the UK, Germany and US could spy on us. So they could know what we’re thinking, what our plans for migration were. But when I finally decided to come to the square I saw that the cause here is good. It was to help and support, not to spy. So, I’ve been coming to this square for three months now. I use the washing machines to clean my clothes, eat and play board games. It’s not like the rest of Athens, it’s a safe place. There are no drugs, no problems, just food and friendship.

(Ahmed, Athens)

We’re part of a group that has started an Arabic printed newspaper, Eed Be Eed [Hand in Hand]. It was started by an old neighbour from Aleppo actually. We decided to have a printed newspaper, something tangible you can hold, that allows you that connection with language when most of your life is in German. We wanted to see it next to the papers in German. There are so many writers and journalists who were heavily censored in Syria and here they are able to express their own opinions. To post a headline like ‘Aleppo is Burning’ may not seem like much, but for us, to state things as we see them so publicly is so important. You know, at the beginning of the revolution in Syria, we used to print leaflets on our private printers to distribute on the streets. If any of us were caught we were gone, that’s it. And now, we print an actual newspaper, at a professional printer – in colour!

(Anas & Muhamad, Berlin)