Get to know the newcomers, activists and volunteers we met in Athens, Berlin and London and their unique experiences of refuge, welcome and the digital city.

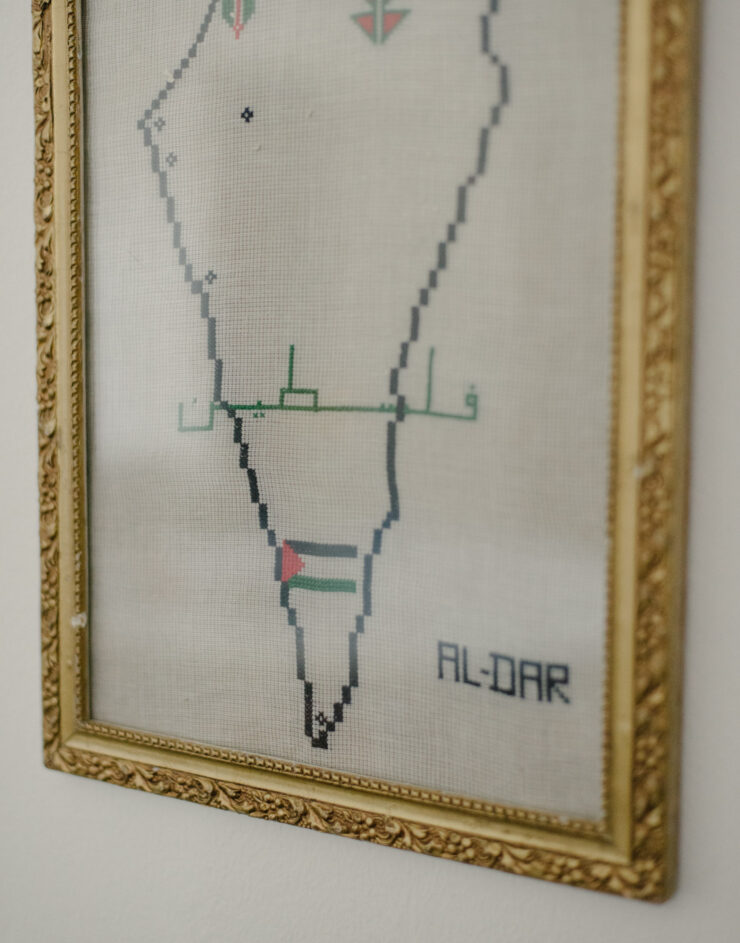

Renée, Al-Dar

Neukölln, Berlin, September 2018

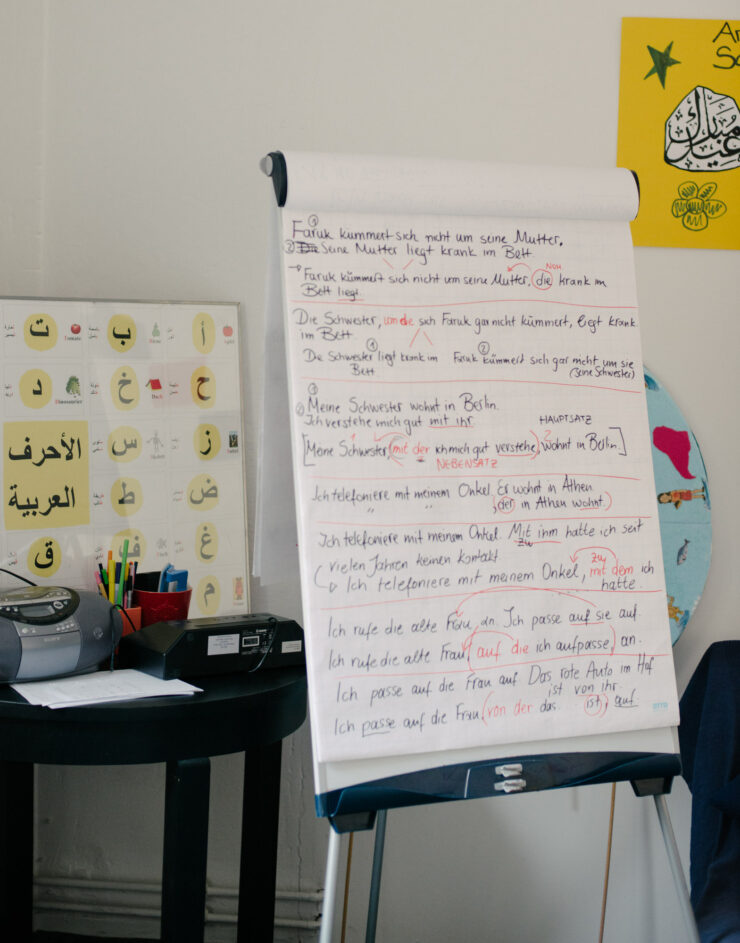

I started in 1978 by providing the first German language course for Arabic women. The families at that time were coming from the war in Lebanon and there was nothing available in Arabic. It quickly became very clear that language was not enough. They had many issues, many questions.

So we started a self-help space for Arabic women, Al-Dar, where they could come together to be able to help each other. We don’t set the agenda, the community of women who come to our space do. We have these open meetings where women discuss issues close to them and the skills or resources they need. We then go about sourcing them. We’ve had typewriting classes, computer lessons, swimming lessons, homework support. Even group activities to learn how to ride a bike!

Different groups of refugees have had very different experiences arriving here. The ones who flew here from Lebanon in the 70s/80s had easier journeys, they just took a flight. But when they arrived they were rejected and isolated. The Syrians and Iraqis now have had very difficult journeys, but once here they found a politically welcoming environment. The Lebanese refugees were concerned with issues of residency, risk of deportation and constant instability. This led to endless other problems, many of them familial, such as divorce and attempts to marry Germans for residency. The Syrians and Iraqis today are dealing with other traumas, whether it is from their journeys or the wars they’ve witnessed and experienced.

(loss)

The digital emerges a lot in our open forums. Parents feel children spend too much time online and have too much access. So we developed a course specifically tailored to helping parents deal with these issues by teaching them how to have a look at browsing histories, how to block certain websites and introduce parental controls. It is important to recognise that this is not an issue that is particular to the Arabic community or refugees. Parents are dealing with this all over the world. We are addressing it using Arabic rather than German, but we speak about it as a global problem not a cultural one.

We have programmes with men as well, we don’t know if we can reach them but we try. We support them to find new roles for themselves, we talk about relationships with their children, the importance of not just love but respect. Because you can love someone but still think you can order them around. This is our most difficult work, but we never communicate this as adapting to or integrating into German society. It is not specific to Arabic culture, it as a gradual democratic transition all around the world. Even in Germany, gender roles were very different only a couple of decades ago. So we don’t speak about civilizations, as if one is better then the rest. This strategy does not work. I always tell them cultures are like living beings, we need to shed our old skin cells all the time no matter what skin we wear.

(home)

It took years for Al-Dar to be legalised and accepted by the German Senate. We’ve done some great things but we are also limited by the laws we can work within. When refugees started to arrive in the 70s, they were given ‘Duldung,’ which literally translates to “temporary toleration extensions” and had to be renewed every 3-6 months. This lasted four decades and entire generations of children were born into this situation. In 1981 it got worse with new restrictions banning refugees from working and their children from going to university. When they finally gave children of ‘Duldung’ permit holders rights to study and work, but they had already lost the motivation… Many of the laws since the 1990s were good, but they were too late. It took so long for politicians to understand how important this was.

The welcoming environment in 2015 was a very positive development, but the problem was that Germans hosted newcomers in their homes without being prepared on what to expect or how to deal with trauma. They expected they would come stay and be thankful all the time. There was no understanding of conflict and its aftermath, of the psychological journey the newcomers were going through. They had lost family, friends, property. They were having to make sense of what they just experienced and what they are now receiving. So then the people who opened their homes, with good intentions, started to withdraw their welcome. In many cases, unfortunately, they turned the other way, to the right. The welcome was genuine but it was not supported well. I believe it was a missed opportunity.